With Jack Frost nipping at our noses, radiators have become our Besties this time of year. From playful crayons to stylized tree silhouettes, these heaters creatively explore linear and geometric forms while fulfilling their mission of keeping our homes toasty!

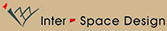

For the young – or the young at heart – here is Tubes Radiatori’s Matitone, literally meaning ‘Large Crayon or Pencil’. This polychromed radiator is perfect for children’s rooms or anywhere that’s looking for a whimsical punch of color. Matitone comes as a neat row of 25 mm (.98”) steel tubes topped by colored tips, set in front of the horizontal manifolds. The colors can be customer-specified for an upcharge or delivered as a random factory mix. The hydronic heater is available from 10 elements, 35.5 cm (13.9″) w, to 15 elements, 53 cm (20.9″) w, and in heights ranging from 140 cm (55.1″) to 200 cm (78.7″).

Tree, Viadurini’s portable electric radiator, will satisfy anyone with a nomadic spirit. Much like a floor lamp, the free-standing heat source is truly plug-and-play. The minimalist heat sculpture is made of 3.5 cm (1.38”) steel tubing, taking up a compact footprint of 60 cm (23.62”) diameter, tapering to 30 cm (11.81”) at the top. At a height of 160 cm (62.99”), it can arguably double as a towel or clothes warmer! Finish options include Matt Ivory Beige or Matt Volcano. It comes with a 150 cm (59”) long braided black cotton cable, pedal switch, and leveling feet. Made in Italy, the lead time is 20-30 days.

UK-based manufacturer Aeon elevates the humble radiator into a design statement. Sporting the sleek profile of a glass-and-steel hallway console, Elixir is actually a high performance heater in disguise. Also available is a coordinating mirror featuring the same angular motif to complete the look. Aeon offers a 20 year warranty on the appliance which comes in brushed matt stainless steel with 2 sizes and wattages – 1200 mm (47.24”) w x 255 mm (10.04”) d x 900 mm (35.43”) h at 3277 W or 1500 mm (59.06”) w x 255 mm (10.04”) d x 900 mm (35.43”) h at 3638 W. Mirrors are 840 mm (33.07”) w x 60 mm (2.36”) d x 630 mm (24.8”) h and 1050 mm (41.34”) w x 60 mm (2.36”) d x 630 mm (24.8”) h, respectively.

Giuly is an award-winning Extraslim radiator from Italian designer Mariano Moroni for Cordivari. The design is an abstraction of the automotive grille, whose utilitarian air intake slots are stylishly reincarnated into towel-warming rails. The low-profile appliance requires a mere a 70-80 mm (2.76”-3.15”) wall clearance. Hydronic systems are available as 520 x 1200 mm (20.47 x 47.24″), 520 x 1590 mm (20.47 x 62.60″) and 620 x 1750 mm (24.41 x 68.90″), while the electric version comes exclusively in the largest format. With 80 colors to choose from, these heaters are guaranteed to work with any color scheme!

The brainchild of Valentina Volpe, Polygon won multiple awards, including the prestigious Red Dot Award. This next-gen radiator allows convenient access and control through mobile devices using home automation platforms like Google Home, Alexa and the Apple HomeKit. Dimmable color changing LEDs are integral to the 3-dimensional design, which comes in both vertical and horizontal configurations. The former is 500 mm (19.69″) w x 1800 mm (70.87″) h x 120 mm (4.72”) d, while the latter is 200 mm (7.87”) d to accommodate a hidden shelf for display (as shown) or storage. The surface can be Glossy, Matt or Rough, with 2-tone finishes in choice of Matt White/Matt Light Grey, Pearl White/Quartz, Matt Light Grey/Agave, Satin Black/Medium Grey, Sable/Agave, or special combinations in other RAL colors.

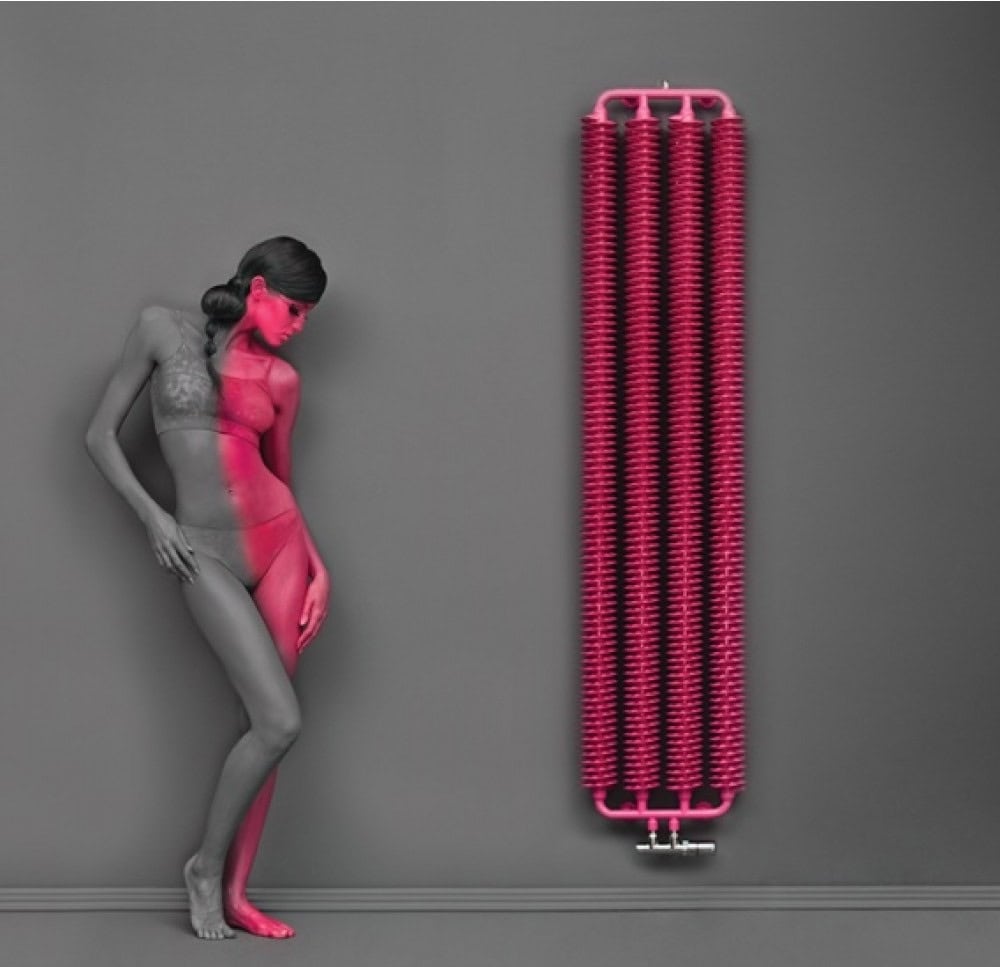

Terma is a Polish manufacturer of heating products. Its popular Ribbon radiator resembles oversized bolts, with the numerous screw-threads providing ample surface area for high-efficiency heat exchange and comes with a 12 year warranty. Sizes for both electric and hydronic model are: 290 mm (11.42”) w x 1800 mm (70.87”) h, 390 mm (15.35”) w x 1800 mm (70.87”) h or 390 mm (15.35”) w x 1920 mm (75.59”) h. The Gloss, Matt or Soft versions are offered in an impressive 66 special and 191 RAL colors.